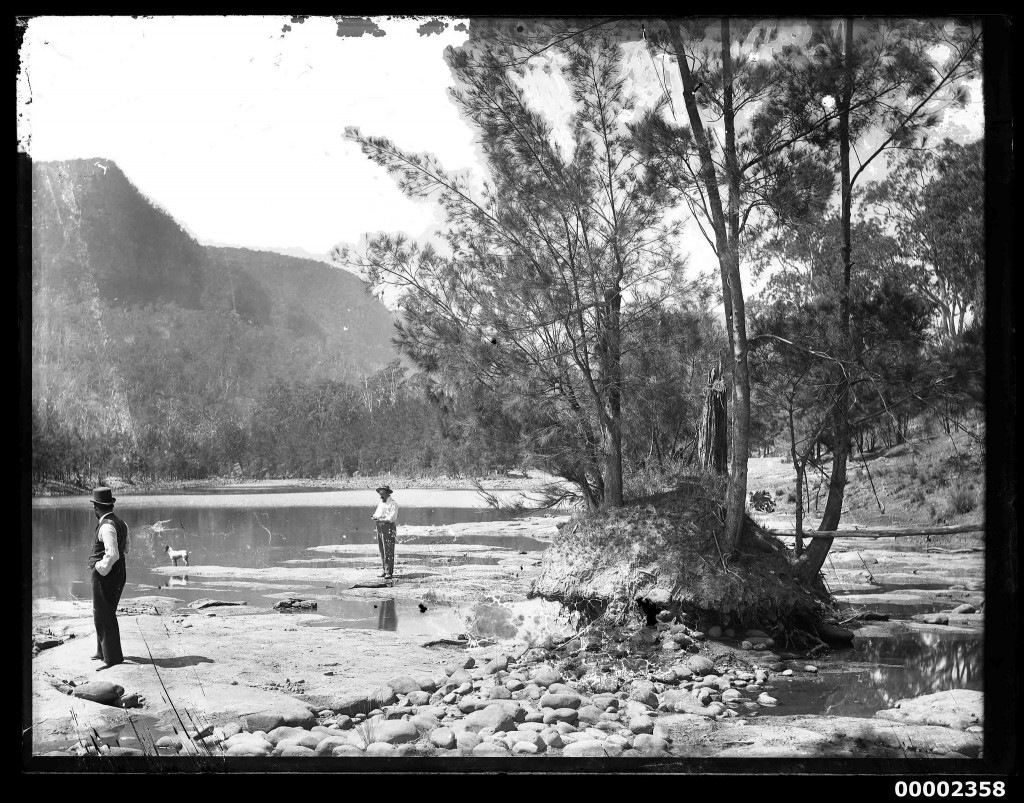

A century ago photographer William Hall captured the beauty and industry of the Hawkesbury River in New South Wales. Nicole Cama followed in his footsteps and fell equally in love with the surrounds.

Singletons Mill c 1900, built in 1834. Courtesy of the William Hall Collection, Australian National Maritime Museum.

SOMETIMES, to truly understand a historical context, you must venture beyond your comfort zone. In late 2012, I discovered in the Australian National Maritime Museum’s collection a spectacular series of glass-plate negatives taken by photographer William Hall. They depicted the lower Hawkesbury River area in New South Wales in about 1900. As I delved deeper and made contact with a local historical society, I realised I had stumbled across a few treasures of Australian photographic history. It was at this point I knew I would have to go outside the museum’s walls. I wanted to re-create a sense of time and place and to visualise lifting up the glass plates and matching them against the curve of the river. I wanted to explore Hall’s Hawkesbury and imagine what travelling the area might have been like for the man behind the glass-plate camera.

First stop on my journey of historical exploration was the heritage-listed Wesleyan Chapel at Gunderman, where I met members of the Dharug and Lower Hawkesbury Historical Society (DLHHS) who assisted in identifying many of Hall’s photographs. Built in 1855, the chapel remained in use for almost 100 years and was restored by the DLHHS in 1986. Travelling the winding Wisemans Ferry Road, my next stop was old Cobham Hall (now Solomon Wisemans Inn), built in 1826 by the famous convict and merchant Solomon Wiseman.

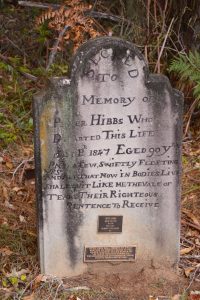

After tea and scones at the historic Settlers Arms Inn at St Albans, I explored Laughtondale Cemetery, where I found the grave of First Fleet seaman Peter Hibbs. Hibbs allegedly sailed with Captain James Cook on HMB Endeavour and was credited in the Windsor and Richmond Gazette of 1890 as being the second Englishman after Sir Joseph Banks to step ashore at Botany Bay in 1770. Hibbs died in 1847, aged 91, and his tombstone bears the inscription:

The area’s Wesleyan Chapel has recently been restored and is open to visitors. Courtesy of Nicole Cama.

Pass a few swiftly fleeting years

And all that now in bodies live,

Shall quit like me the vale of tears

Their righteous sentence to receive…

Exploring the area made me realise how vital the river was, and continues to be, for transportation. As Kate Grenville so cleverly illustrates in her novel The Secret River, there were few roads cut into the steep sandstone escarpments that bordered the river, so the waterway became the lifeblood of the community. From the earliest days of colonial settlement, it was a pathway for further exploration into the interior. Governor Arthur Phillip led three expeditions up the river in an attempt to find land suitable for farming. During these early years of uncertainty, the colony struggled to sustain itself in land considered unfit for agriculture. For the settlers, they faced a challenge that they mostly had neither the expertise nor the resources to undertake.

It was only after Phillip’s tenure as governor that the rich soils of the area became a major food source for the colony. Mills were built to grind grain before it was transported along the river and then down to Sydney. Hall managed to photograph a tidal mill not long before it was destroyed by floods in 1909. Singletons Mill or, as the Australian Town and Country Journal put it, ‘one of the lions of the Hawkesbury’, was built about 1834 near Layburys Creek. After the 1867 floods, the mill fell into disuse and was transformed into a rustic tourist attraction. Local folklore added to its appeal, claiming it was haunted by the ghost of an old miller. Around 1900 — the same time Hall documented the mill’s haunting beauty — Samuel Boughton recorded his impressions in Reminiscences of Richmond, his weekly column from 1903 to 1905 for the Hawkesbury Herald, and described how it was:

… black with age and coal tar … a striking contrast to the pretty cottage alongside of it … yet in days gone by, the mill … was a scene of horror at times. I have it from an “old hand” who labored there and received many strokes of the cat to waken him up when dozing after sixteen hours’ hard work. “We worked day and night,” he said; “the better the harvest, the more work for us. The wheat was brought from the McDonald, the Colo, the Mangrove, and we handled it all. So, also, when ground, we landed the flour into the schooners for Sydney.

~ quoted in A Hawkesbury Story by Valerie Ross (Library of Australian History, 1981)

The headstone of First Fleeter Peter Hibbs still stands in Laughtondale Cemetery. Courtesy of Nicole Cama.

Added to this gloomy illustration of forced labour and devastating floods, the area’s secluded nature produced still more disparaging attitudes toward

the river and its people. In the seminal book, Hawkesbury River History: Governor Phillip, Exploration and Early Settlement, Jocelyn Powell notes that James Atkinson wrote in 1826 of the ‘thoughtless and negligent’ ways of the settlers, who spent much of their spare time gripped by ‘intoxication and debauchery’. Powell also notes that the Reverend Alfred Glennie wrote in 1860 that the area, though beautiful, was isolated and suffered a ‘total absence of suitable society’.

Despite these negative portrayals and the general hardships faced by settlers in the area, there were others whose transient experiences were to feed the mystique surrounding the river for many years to come. English novelist Anthony Trollope wrote of the river’s unparalleled beauty in 1873, concluding that it transcended the Rhine and Mississippi rivers:

The Hawkesbury has neither castles nor islands, nor has it bright clear water like the Rhine. But the headlands are higher and the bluffs are bolder, and the turns and manoeuvres of the course which the waters have made for themselves are grander, and to me more charming…

Inspired by Trollope’s account, another traveller published a stirring tribute in the Illustrated Sydney News on 22 November 1873:

Lying within about forty miles of our city, the sylvan loveliness of this charming river is as little known as if it were situated in Germany, and the time is fast arriving when we dwellers in Sydney should begin to arouse from our apathy, and take an interest in the beauty which surrounds us.

Over the decades writers have described the beauty of the river as they experienced the Hawkesbury the way the first settlers did, that is, from the water. Their romanticised observations fed the myth of the Hawkesbury as a silent river shrouded in mystery; a concept that endures today. Yet for the farmers and merchants who settled in the area looking to make their way in the coastal trade, the river formed an essential part of the social, cultural and economic fabric of the Hawkesbury community.

Two men and a dog possibly standing on the Hawkesbury River NSW, 1880-1909. Courtesy of the William Hall Collection, Australian National Maritime Museum.

Hall’s photographs depict the Hawkesbury during a time of transition, not quite its former colonial outpost or its current residential haven away from Sydney. There was a time when the river was teeming with vessels and the mills worked day and night because, reported the Windsor and Richmond Gazette on 17 February 1900, ‘the Hawkesbury was the colony’s cornfield’. Yet this must have been before Hall, because his images appear ghost-like; a lone boat drifts passed Bar Island, and Singletons Mill languidly deteriorates, no longer of any use to anyone in its dying days. These remnants reflect a moment in our history when the colony struggled to find a food source and the Hawkesbury River opened a vital lifeline for settlers. Even now, though the mill has been reduced to a few rocks and old mansions have been converted to inns, there is still a grave of a First Fleeter, the Wesleyan Chapel has been restored and stories continue to be told.

About 112 years after Governor Phillip explored the river, William Hall journeyed through the scenery and captured vestiges of early settlement just before they became ruins. And about 112 years after Hall trod the riverbank, I too found traces of the early settlers and witnessed the beauty of the Hawkesbury River with my own eyes, beyond the glass-plate negative.

✻ Thank you to Kay Williams from the DLHHS for her tireless efforts identifying and researching Hall’s photographs and for her time taking Nicole Cama, a curatorial assistant at the Australian National Maritime Museum, around the beautiful area.

NOTE: This article was first published in Inside History magazine, Issue 18, (Sep–Oct 2013), pp 54–56 and on their blog. Reproduced courtesy of Inside History magazine.