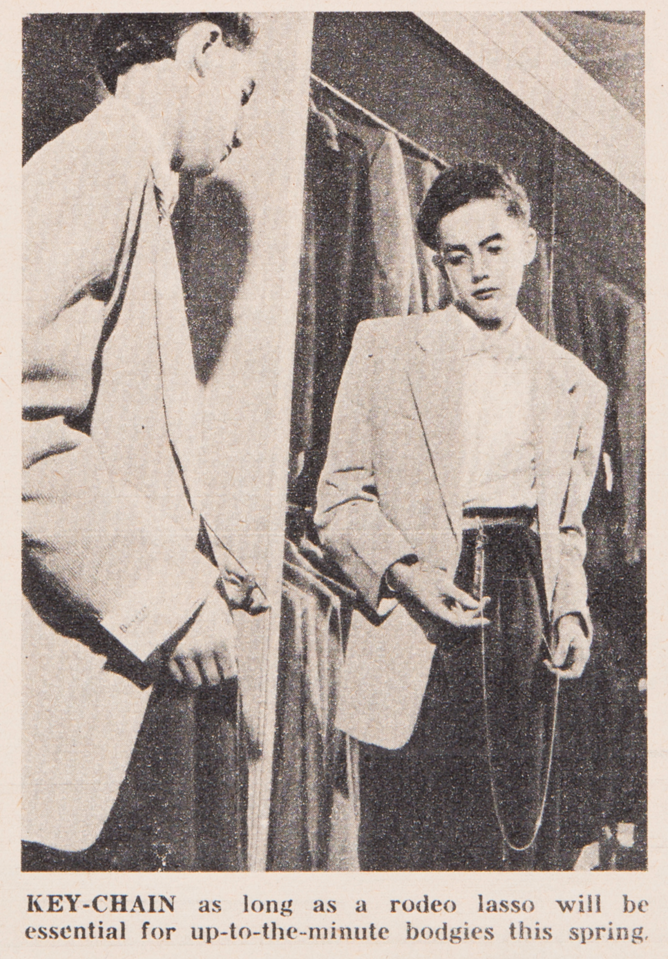

Key-chain will be essential for up-to-the-minute bodgies this spring, July 1951. State Library of NSW

Ever heard of the term bodgie? What about widgie? When we think of great social change, people often cite the 1960s as a decade of transformation. But toward the end of World War II in the 1940s, a subculture emerged among Sydney’s youth – they called themselves bodgies and widgies and drew their inspiration from African American culture. I spoke with Mitch about it on 2SER this morning.

A new entry has just been published on the Dictionary of Sydney by writer Clem Gorman, and it details the development of what Gorman terms a ‘sensual revolution’ among Sydney’s youth during the 1940s. Young men were wearing loose-fitting jackets, brightly coloured shirts, suede shoes and pants with key chains dangling from their belts. Young women cut their hair short and wore jeans. They called themselves bodgies and widgies and were directly influenced by African American servicemen who were among the thousands of US soldiers who congregated in the many clubs and streets of Kings Cross, Surry Hills and Darlinghurst during World War II.

American soldiers laughing at a performance by comedian Joe E Brown at an army camp in New South Wales 18 March 1943, State Library of Victoria

This cultural movement and its new fashions and music marked the beginning of subsequent waves African American influences in Australia, such as rock and blues music, gospel and hip-hop. Gorman notes the bodgie movement sprung out of ‘a rejection of the dry, bloke, anti-emotional male culture of the inherited British tradition’. Although African American culture had entered Sydney during the 1920s, it wasn’t until 1943, when black GIs came Sydney bringing their fashions and rhythm and blues music.

Gorman collected much of his research from interviews conducted with men and women who identified as bodgies and widgies in Sydney during the 1940s and 1950s. He goes into great detail about the bodgie fashions, music tastes and cultural pursuits. Their suits, for example, were influenced by suits worn by young African Americans in the first half of the 20th century, which in turn were influenced by gunnysack clothing worn on cotton plantations. Their suits included padded shoulders and were generally loose fitting.

If you’re a square you’ll have to get hep to bodgey language, March 1951. State Library of NSW

Some of the bodgies interviewed reminisced how they not only adopted the fashions of African American GIs, they also set out to emulate their body language, walk and slang speech. One called this transformation ‘a statement, a kind of slap in the face to the powers that be’. Another feature which attracted young working-class Australians to the visiting African Americans was their dancing, which emphasised fluidity in the hips, free arms, tapping feet and a joyful attitude, a huge departure from the more traditional dances they were exposed to like the foxtrot.

According to some of those interviewed, there was one man who embodied all the ‘coolness’ of bodgie and was known as the ‘sharpest cat in the Cross’. But none of the interviewees seem to agree on his name, which was given variously as Kenny Lee, Donny Mannion or several Greek and Italian names. Whoever he was, according to his contemporaries he was incredibly good looking, successful with women, hip, sharp, cool and tough. Gorman concludes it’s possible this man was a myth; a figment created to ‘represent an idealised version of ‘bodgiedom’ which no individual could meet’.

On that note, I’ll leave you with some bodgie language to resurrect in common usage. ‘Guzzling Foam’ meant having milkshakes, for the widgies ‘Etching the edges’ meant applying lipstick, ‘the Royal smooth’ meant having a steady girlfriend, and ‘His plates don’t beat’ meant whoever ‘he’ is, he doesn’t understand. Make sure you check out Clem Gorman’s fantastic article in the Dictionary of Sydney!

Listen to my segment at 2SER radio and read the original article by Clem Gorman at the Dictionary of Sydney. For other interesting segments, see my Dictionary of Sydney project post and visit the Dictionary of Sydney blog.