Australian Engineers making small stoves for the coming winter, 1917-18. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, PXB 215/126

In his report on the activities of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) Research Section, inventor William H G Geake noted that it was not until 1916 that World War I was deemed an ‘Engineer’s war’.1W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 118. The new form of industrialised warfare witnessed on the battlefront created a sense that the war could be won through innovation. Faced with this reality, the horror stories of trench warfare and devastating losses such as the Gallipoli Campaign, some Australians channelled their energies toward devising innovative solutions to aid the war effort.

Often their creative endeavours never came to fruition as bureaucratic hurdles and restrictive legislation blocked their efforts, and many inventions were never registered with the Patent Office. Despite this there were many interesting developments proposed, some of them improvised during the deadly fire at the battlefront, and some of them back home in Australia. To an extent, this creative ingenuity witnessed on the battlefront informed part of what has been commonly labelled the ‘Anzac spirit’, that is, the characterisation of the men of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps as inherently resourceful and innovative.2Much has been written about this topic (and more critically the ‘Anzac myth’). See Australian War Memorial for a brief summary, accessed 29 March 2015, see also State Library of NSW’s reading list, accessed 29 March 2015. This idea has also been held up as an illustration of an Australian ‘national character’, and this belief in the inventiveness of Australians remains entrenched to this day, 100 years after the war.

‘Aussie’ Innovation

The English novelist H G Wells recognised this new ‘modern war’ as a ‘struggle of gear and invention’.3‘What Modern War Is’, 12 June 1915, The Argus, p. 17. In terms of technological innovation in the military sphere, Australia relied heavily on Britain. Despite this, there were calls for Australians to innovate and contribute to the war effort. One Australian newspaper noted: ‘The Germans mobilise their scientists and physicists for military purposes as they mobilised their whole nation. The war is more and more becoming a matter of science’.4‘New Ideas for the War’, 24 September 1915, The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser, p. 6. Victorian Governor Arthur Stanley also chimed in, praising the work of the University of Melbourne’s Professor William Osborne, who later played a role in developing a respirator for protection against poisonous gas. Stanley spoke of the importance of ‘mobilising the nation’s brains’ as a crucial resource for the war effort.5‘Science and war’, 16 October 1915, The Argus, p. 20. See also Tim Sherratt, ‘Anzac Brains – Prologue’, Chapter 4 in Atomic Wonderland: Science and Progress in Twentieth Century Australia, 2003 (PhD), Australian National University Two months later Osborne emphasised the role of science in the war effort and proposed the establishment of a national research institute to Prime Minister William M Hughes, an idea which formed the foundations for the CSIRO.6‘Federal Research’, 23 December 1915, The Argus, p. 10.

Yet despite calls to mobilise brainpower, most inventions submitted for consideration did not make it to Britain’s War Office, and of those that did even fewer were developed and adopted. This seemed to cause dismay among the Australian press. One dramatically claimed that, despite their ‘creative genius’, inventors ‘go unrewarded to a pauper’s grave’.7 ‘The Reward of Brains’, 15 August 1915, Direct Action, p. 2. One lamented about how ‘our inventors, creators, scientists, engineers, chemists, and discoverers are immobilised, all these months unwanted and unheard’.8‘Brains and Bayonets’, 9 August 1915, The Register, p. 6. Another stated Australians had a natural ‘spirit of initiative’ and that inventions produced during the war ‘were more numerous in proportion to Australia’s population than those of any other nation’, but had received little credit.9‘Our Inventors’, 14 February 1922, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 8.

In addition to the lack of recognition, the government introduced a suite of measures under the War Precautions Act 1914, which included the War Precautions (Patents) Regulations 1916. Under this legislation, every application was screened by a Patents Inquiry Board, which included members appointed by the Minister for Defence. The board had specific powers to decline an application if it was deemed ‘detrimental to the public safety or the defence of the Commonwealth or might otherwise assist the enemy or endanger the successful prosecution of the war’.10War Precautions (Patents) Regulations 1916, 3 (5), 12 July 1916, ComLaw, accessed 20 March 2015.

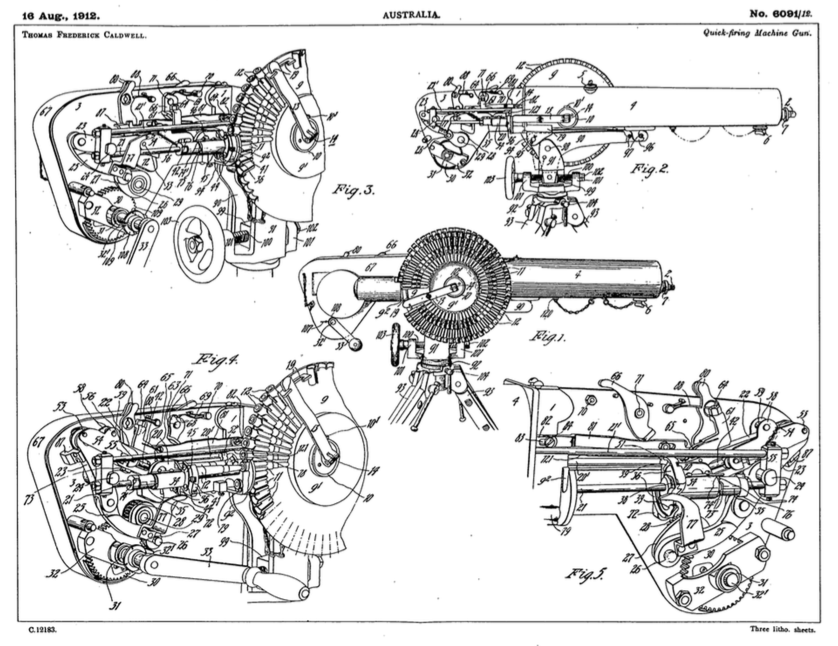

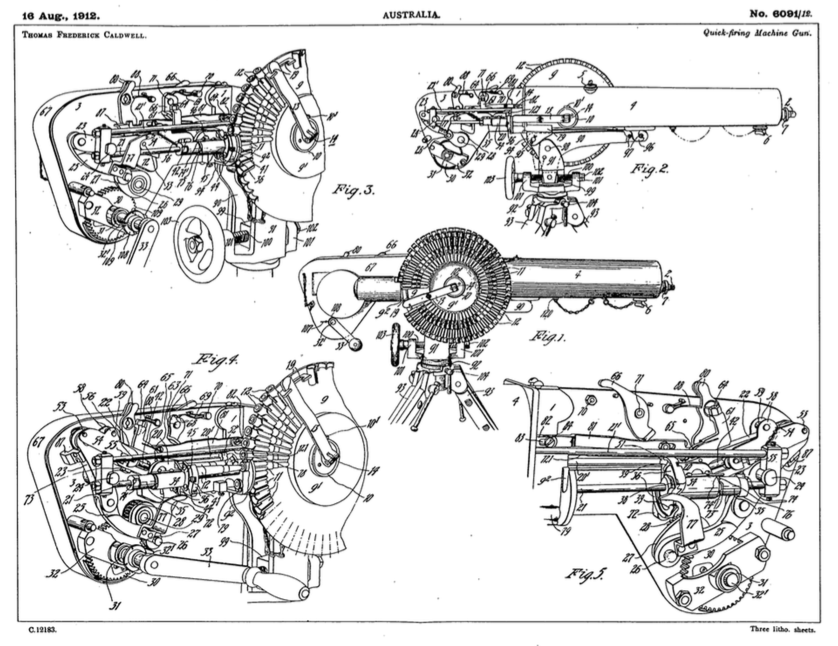

As a result of these social and legal hurdles, some Australians offered their inventions to the Department of Defence only to find them fall by the wayside. A well known example of this was Private Lance de Mole’s early designs for a military tank. However other stories have emerged that merit their own spotlight. On 16 August 1912, Melbourne’s Thomas Frederick Caldwell submitted a patent application for ‘An improved quick-firing machine gun’.11Application numbers 6091/12, 16 August 1912, accessible via AusPat. The mechanical engineer declared his invention was ‘exceedingly light, simple and durable in construction and perfectly easy to operate’. Trials of the gun took place in February 1914, with 6000 live cartridges and 25 000 blanks fired at an estimated 1000 shots per minute.12‘Australian Machine Gun’, 4 February 1914, The Argus, p. 7. When both Australian and British authorities failed to support the invention, the gun was allegedly almost sold to a German armament firm in July 1914 before the declaration of war halted negotiations.13‘Australian Machine Gun’, 14 November 1914, Leader, p. 5. In 1915, the gun was reportedly sold to a London firm for £55 000 in cash with a £4 per gun royalty on all guns manufactured in Britain and 10 per cent of foreign rights and licences.14‘Caldwell Machine Gun Co.’, 20 March 1915, The Argus, p. 21. Also ‘Caldwell Machine Gun’, 27 March 1915, Poverty Bay Herald, p. 4.

Patent drawings for Caldwell’s quick-firing machine gun, no. 6091/12, 16 August 1912. AusPat, IP Australia.

In stark contrast to Caldwell’s instrument of destruction is one rare example from a female inventor. Myra Juliet Taylor née Farrell lived in Sydney and registered many patents during her lifetime, with many of her inventions forming in her dreams.15One newspaper claimed she registered 26 patents, ‘For chest troubles’, 23 December 1928, Sunday Times, p. 19. Another newspaper claimed it was 24, ‘Australia’s Woman Inventor’, 20 April 1916, Woman Voter, p. 3. Sixteen of Myra Juliet Farrell/Taylor’s patents are accessible via AusPat, for example application numbers 2575/05, 133/11, 16797/15 and 27026/30. See also ‘The talk of the town’, 20 May 1916, The Mirror of Australia, p. 7. In June 1915, as a widow with a young family and a reportedly ‘strong patriotic’ impulse, Taylor devised a barricade designed to repel enemy rifle and machine-gun fire and reduce the impact of shells.16‘Woman Inventor’, 25 August 1915, The Scrutineer and Berrima District Press, p. 4; ‘Woman Inventor’, 26 August 1915, Guyra Argus, p. 4; ‘Woman Inventor’, 28 August 1915, Western Age, p. 4. The ‘defence fence’ was ‘under the consideration of the Defence Department’ and in the meantime, her ‘surgical belt and binder for use in military hospitals’ had allegedly been accepted.17‘Many Inventions’, 29 September 1915, Warwick Examiner and Times, p. 3. However, a report in May 1916 noted that ‘no practical use has been made’ of the fence, going further by asserting that despite Taylor’s prolific career the reason for the rejection ‘appears to be that the inventor is a woman’.18‘The talk of the town’, 20 May 1916, The Mirror of Australia, p. 7.

What about the Navy?

Despite the many inventions that went unnoticed, there are examples of inventions that were eventually patented, though not necessarily employed in the trenches. Described as having a ‘genius for invention’, John Saumarez Dumaresq was born in Sydney and captured the attention of the British Admiralty years before the war started.19David Stevens, In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One, (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 250. Between 1902-04, he developed a device to improve gunnery accuracy; a trigonometric slide-rule calculator which became known as the ‘Dumaresq’. It consisted of a base plate with a circular disc resting and pivoting centrally to it.

In a letter from the British Admiralty on 26 July 1904, Dumaresq was free to patent his invention but once it was registered, it was to be ‘absolutely assigned to the Secretary of State for War’.20Dumaresq file, Sea Power Centre – Australia, Canberra. On 15 August 1904 Dumaresq registered an English patent for his invention, stating its purpose:

…is mainly to provide an instrument for giving rapidly the required rate of change of range and the deflection necessary for keeping the line of sight of a gun or battery of guns at such an angle both in a vertical and horizontal plane to the axis of the gun as to cause the projectiles to continuously fall at or near the object aimed at…21Number GB190417719A, Espacenet®, accessed 30 March 2015.

According to Royal Australian Navy historian, David Stevens, when the Dumaresq was ‘set with the courses of the firing ship and the target ship, and the target’s bearing’ it ‘indicated both the rate of change of range and deflection’.22David Stevens, In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One, (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 250. There were many iterations of the Dumaresq, however, each one was developed from the initial model and formed a key gunnery instrument in Australia’s new ‘Grand Fleet’ in 1914.23David Stevens, In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One, (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 250. See also Tony Lovell, ‘Dumaresq’, The Dreadnought Project, 21 March 2014, accessed 30 March 2015. Though Dumaresq held a patent on the device, he sought no profit from its production and was paid a total of £1500 as a one-off payment from the Admiralty.24David Stevens, In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One, (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 250.

Message in a…Rocket?

Geake with one of the inventions, 16 January 1918, Sydney Mail, p. 10. Trove, National Library of Australia

After he enlisted in the AIF as an engineer, William H G Geake invented a bomb throwing device with civilian Alfred Salenger.25Peter Burness, ‘Geake, William Henry Gregory (1880–1944)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1981, accessed 29 March 2015. It came to the attention of the Ministry for Munitions in London and in 1917, Geake was ‘loaned’ to the British Inventions Board and then appointed head of the AIF Research Section, which had been established in November 1916.26W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 118.

Despite the initial doubts of the British authorities, the AIF Research Section proved their worth and within three months were allotted their own experimental grounds in Esher in Surrey, England.27W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 119. Geake wrote of ‘the resourcefulness and instinctive ingenuity of the Australian soldier’ as he and his team developed (to name a few) the: ‘Message Carrying Rocket’, ‘Improved Machine Gun Belt’, ‘Impact Hand Grenade’, ‘Smooth Bore Howitzer’, ‘Floating Flare Shell For Naval Use’, ‘Non-Inflammable Petrol Tank’, ‘Rod Gun’, ‘Magazine for 303 Rifle’ and ‘Stream Lined Stoke Shell’.28W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 119-22.

Message Rocket invented by Lieutenant W H G Geake, AIF Research Section c 1917, Australian War Memorial, RELAWM04381

Geake’s most successful invention, the Message Carrying Rocket, was made of steel with a range of up to two kilometres.29W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 122. Peter Burness, ‘Geake, William Henry Gregory (1880–1944)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1981, accessed 29 March 2015. See also Message Rocket at Australian War Memorial, accessed 29 March 2015. It included a propellant, whistle at the tip and a two-piece tube which carried the smoke and flare composition as well as a receptacle for carrying messages.30Message Rocket at Australian War Memorial, accessed 29 March 2015. Described by one Australian newspaper as the ultimate example of ‘Digger brain and originality’, Geake continued his work with the AIF Research Section and his rocket was in use on the Western Front until the end of the war.31‘Inventors Active’, 26 June 1919, The Newcastle Sun, p. 5.

The Melbourne University Respirator

At 5 pm on 22 April 1915 German forces released thick green-yellow clouds of deadly chlorine at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium. It was the first large scale use of poison gas on the Western Front and caused consternation across the other side of the world as Australian newspapers reported on the ‘terrible carnage’ and ‘dastardly tactics’ of the Germans.32‘Flanders Battles’, 27 April 1915, The Ballarat Star, p. 1.

Scientists at the University of Melbourne responded and developed a form of protection for this new type of warfare. Professors David Masson, William Osborne and Thomas Laby had a makeshift trench dug in the university grounds and filled with poisonous gas as they tested their prototype.33Ernest Scott, Chapter VII ‘The Equipment of Armies’ in Volume XI, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 7th edition, 1941, p. 253 and Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 398. On 21 June 1915 they submitted their report to the Department of Defence recommending the use of their apparatus which consisted of a metal canister filter, chemical purifier, air tubes, mouthpiece for inhalation, nose clips and eye goggles.34Ernest Scott, Chapter VII ‘The Equipment of Armies’ in Volume XI, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 7th edition, 1941, p. 252.

Though the British War Office communicated that 300 000 masks of their own were being sent to the front, Governor-General Ronald Crauford Munro Ferguson ordered 10 000 Melbourne University Respirators be manufactured.35Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 399. In the meantime, a report from the War Office stated that despite its ‘excellent make and finish’ the respirator had several deficiencies and would not be required.36Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 400. In the end, it is not clear as to what extent the respirator was adopted in the field as the 10 000 masks made their way France in July 1916.37Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 401. Its general failure has been attributed to a mixture of bureaucracy, the desire for a standardised military kit and Australia’s isolated position from the battlefront.38Arthur G Butler, Chapter I ‘Chemical Warfare’ in Volume III, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 1st edition, 1943, p. 27, Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 402 and Eric Endacott, ‘Inventing to Win the War. Amateur Inventors and the Australian Home Front, 1914-1918’, Honours thesis, Deakin University 2012, p. 26. Despite this, it is possible elements of their invention was incorporated in the development of the British box respirator.39Eric Endacott, ‘Science and Technology (Australia)’, 8 October 2014, 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer and Bill Nasson, eds., Freie Universität Berlin. After the war, the respirator was used as political tool to demonstrate the value of scientific research to defence.40Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 392.

‘The Transporter’

One wonders whether the Germans would let Alexander Worsfold and his clever son go from the factory to “fill a dug-out”.41‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7.

In 1915 Alexander Worsfold, a manufacturer from the Sydney suburb of Arncliffe, expressed his frustration to a reporter from The Sydney Morning Herald. He claimed he had ‘been trying for months to interest the Defence Department in my inventions…If I cannot make those things, I can go, and with my son, fill a dug-out, or perhaps at the seat of war there may be more opportunity for assisting my country with my technical knowledge’.42‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7. Despite a testimonial from one of Australia’s great inventors, aeronautical pioneer Lawrence Hargrave, it seemed Worsfold’s new ambulance stretcher was not, as confirmed by the SMH reporter’s closing remark above, receiving the attention it deserved.43‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7. Yet Worsfold’s stretcher eventually became the only Australian invention developed from the home front that was adopted on the battlefront.44Eric Endacott, ‘Inventing to Win the War. Amateur Inventors and the Australian Home Front, 1914-1918’, Honours thesis, Deakin University 2012, p. 26 and p. 41.

‘The Transporter’, as it became known, was designed to reduce the ‘difficulties of transport of provisions, munitions, comforts, etc., from the field base to the trench, and of wounded soldiers from the trench to the field hospital.’45‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7. It was made of mountain ash, included a pair of bicycle wheels, and resembled a snow sledge – a remnant of Worsfold’s earlier design for sledges used by explorer Douglas Mawson’s in the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914).46‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7 and Margaret Simpson, ‘Centenary of Mawson’s 1911 Antarctic Expedition – Part 2 – The riddle of the sledges’, 7 December 2011, Powerhouse Museum blog. Indeed Mawson reportedly commiserated with a disappointed Worsfold writing, ‘In your particular line I judge that you have no peers in Australia, and feel certain that there are many openings for your genius in producing paraphernalia in connection with war requirements’.47‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7.

After the initial report of Worsfold’s invention appeared in the SMH, a follow-up article published a month later revealed that there had been ‘interesting developments’ in his story.48‘Who is Worsfold?’, 2 October 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7 Worsfold had been working at Victoria Barracks army base in Paddington day and night, testing and improving his ‘life-saving device’.49‘Who is Worsfold?’, 2 October 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7 His contraption had been reduced in weight, was capable of carrying a quarter of a ton and had been inspected by representatives from the Department of Defence.50‘Who is Worsfold?’, 2 October 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7 Though it was initially rejected, Worsfold’s Transporter was in use in France by 1917.51Eric Endacott, ‘Inventing to Win the War. Amateur Inventors and the Australian Home Front, 1914-1918’, Honours thesis, Deakin University 2012, p. 36.

9th Australian Field Ambulance, 1916, Worsfold appears in the second row third from the right, Australian War Memorial, P01718.001

Worsfold joined the AIF on 10 August 1915 as a Private in the 9th Field Ambulance and embarked on HMAT Argyllshire in Sydney on 11 May 1916.52Service no. 12096. National Archives of Australia: B2455, WORSFOLD A. He contracted the flu and was admitted to hospital in December 1916 and by June 1918 he had been transferred to the AIF Research Section Headquarters in London, during which time he invented a sound-ranging apparatus and was then promoted to 2nd Lieutenant in April 1919.53Service no. 12096. National Archives of Australia: B2455, WORSFOLD A. See also Ernest Scott, Chapter VII ‘The Equipment of Armies’ in Volume XI, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 7th edition, 1941, p. 251 and ‘Alexander Worsfold’, The AIF Project, accessed 23 March 2015. He was repatriated to Australia on 18 October 1919. During his career, Worsfold registered numerous patents, such as: ‘Improved movable seat appliances for dog-carts, gigs and such like vehicles’ (1905), ‘Improved hollow concrete block to be used in the construction of walls and other structures’ (1921), ‘Improved type of autoclave for soap making, steam distillation and analogous purposes’ (1922) and ‘Improved system of construction for wireless telegraphic masts’ (1922).54Application numbers 4323/05, 356/21, 10451/22 and 10499/22 respectively. Patents accessible via AusPat.

Conclusion

In the end, even though most inventions and innovations did not entail registered patents, they stand as a testament to the efforts and creativity of these Australians. Despite the missed opportunities, restrictive procedures and difficult times, many Australians applied their creativity in their own distinctive ways. Resourceful ingenuity was not just a virtue particular to the Aussie ‘digger’, and if anything was going to win the war it was not just the ‘Anzac spirit’ at the battlefront, it was also the brilliant minds and steadfast determination of those at home.55Roy MacLeod, ‘From ‘Arsenal’ to ‘Munitions Supply’: Revisiting the Experience of the First World War’ in Frank Cain ed, Arming the Nation: A History of defence science and technology in Australia, (Canberra: Australian Defence Studies Centre, 1999), p. 11. See also ‘Brains wanted for Victory’, 23 August 1915, Geelong Advertiser, p. 3.

This article was originally published by Intellectual Property Australia as part of a project to investigate IP rights during World War I. Read the original article. Reproduced here courtesy of IP Australia.

See also: The Anzac brand and Symbols of support and the aesthetic of war

References

| ↑1, ↑26 | W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 118. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Much has been written about this topic (and more critically the ‘Anzac myth’). See Australian War Memorial for a brief summary, accessed 29 March 2015, see also State Library of NSW’s reading list, accessed 29 March 2015. |

| ↑3 | ‘What Modern War Is’, 12 June 1915, The Argus, p. 17. |

| ↑4 | ‘New Ideas for the War’, 24 September 1915, The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser, p. 6. |

| ↑5 | ‘Science and war’, 16 October 1915, The Argus, p. 20. See also Tim Sherratt, ‘Anzac Brains – Prologue’, Chapter 4 in Atomic Wonderland: Science and Progress in Twentieth Century Australia, 2003 (PhD), Australian National University |

| ↑6 | ‘Federal Research’, 23 December 1915, The Argus, p. 10. |

| ↑7 | ‘The Reward of Brains’, 15 August 1915, Direct Action, p. 2. |

| ↑8 | ‘Brains and Bayonets’, 9 August 1915, The Register, p. 6. |

| ↑9 | ‘Our Inventors’, 14 February 1922, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 8. |

| ↑10 | War Precautions (Patents) Regulations 1916, 3 (5), 12 July 1916, ComLaw, accessed 20 March 2015. |

| ↑11 | Application numbers 6091/12, 16 August 1912, accessible via AusPat. |

| ↑12 | ‘Australian Machine Gun’, 4 February 1914, The Argus, p. 7. |

| ↑13 | ‘Australian Machine Gun’, 14 November 1914, Leader, p. 5. |

| ↑14 | ‘Caldwell Machine Gun Co.’, 20 March 1915, The Argus, p. 21. Also ‘Caldwell Machine Gun’, 27 March 1915, Poverty Bay Herald, p. 4. |

| ↑15 | One newspaper claimed she registered 26 patents, ‘For chest troubles’, 23 December 1928, Sunday Times, p. 19. Another newspaper claimed it was 24, ‘Australia’s Woman Inventor’, 20 April 1916, Woman Voter, p. 3. Sixteen of Myra Juliet Farrell/Taylor’s patents are accessible via AusPat, for example application numbers 2575/05, 133/11, 16797/15 and 27026/30. See also ‘The talk of the town’, 20 May 1916, The Mirror of Australia, p. 7. |

| ↑16 | ‘Woman Inventor’, 25 August 1915, The Scrutineer and Berrima District Press, p. 4; ‘Woman Inventor’, 26 August 1915, Guyra Argus, p. 4; ‘Woman Inventor’, 28 August 1915, Western Age, p. 4. |

| ↑17 | ‘Many Inventions’, 29 September 1915, Warwick Examiner and Times, p. 3. |

| ↑18 | ‘The talk of the town’, 20 May 1916, The Mirror of Australia, p. 7. |

| ↑19, ↑22, ↑24 | David Stevens, In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One, (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 250. |

| ↑20 | Dumaresq file, Sea Power Centre – Australia, Canberra. |

| ↑21 | Number GB190417719A, Espacenet®, accessed 30 March 2015. |

| ↑23 | David Stevens, In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War One, (South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 250. See also Tony Lovell, ‘Dumaresq’, The Dreadnought Project, 21 March 2014, accessed 30 March 2015. |

| ↑25 | Peter Burness, ‘Geake, William Henry Gregory (1880–1944)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1981, accessed 29 March 2015. |

| ↑27 | W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 119. |

| ↑28 | W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 119-22. |

| ↑29 | W H G Geake, ‘Activites of the AIF Research Section’, Sabretache: the journal of the Military Collectors Society of Australia, 1978, volume 19, number 2, p. 122. Peter Burness, ‘Geake, William Henry Gregory (1880–1944)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 1981, accessed 29 March 2015. See also Message Rocket at Australian War Memorial, accessed 29 March 2015. |

| ↑30 | Message Rocket at Australian War Memorial, accessed 29 March 2015. |

| ↑31 | ‘Inventors Active’, 26 June 1919, The Newcastle Sun, p. 5. |

| ↑32 | ‘Flanders Battles’, 27 April 1915, The Ballarat Star, p. 1. |

| ↑33 | Ernest Scott, Chapter VII ‘The Equipment of Armies’ in Volume XI, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 7th edition, 1941, p. 253 and Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 398. |

| ↑34 | Ernest Scott, Chapter VII ‘The Equipment of Armies’ in Volume XI, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 7th edition, 1941, p. 252. |

| ↑35 | Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 399. |

| ↑36 | Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 400. |

| ↑37 | Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 401. |

| ↑38 | Arthur G Butler, Chapter I ‘Chemical Warfare’ in Volume III, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 1st edition, 1943, p. 27, Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 402 and Eric Endacott, ‘Inventing to Win the War. Amateur Inventors and the Australian Home Front, 1914-1918’, Honours thesis, Deakin University 2012, p. 26. |

| ↑39 | Eric Endacott, ‘Science and Technology (Australia)’, 8 October 2014, 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer and Bill Nasson, eds., Freie Universität Berlin. |

| ↑40 | Katrina Dean, ‘Demonstrating the Melbourne University Respirator’, Australian Journal of Politics & History, September 2007, Volume 53, Issue 3, p. 392. |

| ↑41, ↑42, ↑43, ↑45 | ‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7. |

| ↑44 | Eric Endacott, ‘Inventing to Win the War. Amateur Inventors and the Australian Home Front, 1914-1918’, Honours thesis, Deakin University 2012, p. 26 and p. 41. |

| ↑46 | ‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7 and Margaret Simpson, ‘Centenary of Mawson’s 1911 Antarctic Expedition – Part 2 – The riddle of the sledges’, 7 December 2011, Powerhouse Museum blog. |

| ↑47 | ‘Who is Worsfold?’, 4 September 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7. |

| ↑48, ↑49, ↑50 | ‘Who is Worsfold?’, 2 October 1915, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 7 |

| ↑51 | Eric Endacott, ‘Inventing to Win the War. Amateur Inventors and the Australian Home Front, 1914-1918’, Honours thesis, Deakin University 2012, p. 36. |

| ↑52 | Service no. 12096. National Archives of Australia: B2455, WORSFOLD A. |

| ↑53 | Service no. 12096. National Archives of Australia: B2455, WORSFOLD A. See also Ernest Scott, Chapter VII ‘The Equipment of Armies’ in Volume XI, C E W Bean ed., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, 7th edition, 1941, p. 251 and ‘Alexander Worsfold’, The AIF Project, accessed 23 March 2015. |

| ↑54 | Application numbers 4323/05, 356/21, 10451/22 and 10499/22 respectively. Patents accessible via AusPat. |

| ↑55 | Roy MacLeod, ‘From ‘Arsenal’ to ‘Munitions Supply’: Revisiting the Experience of the First World War’ in Frank Cain ed, Arming the Nation: A History of defence science and technology in Australia, (Canberra: Australian Defence Studies Centre, 1999), p. 11. See also ‘Brains wanted for Victory’, 23 August 1915, Geelong Advertiser, p. 3. |